Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease of the airways characterised by recurrent episodes of wheezing, breathlessness, chest tightness, and coughing, particularly at night or early morning. These episodes are associated with variable airflow obstruction that is often reversible either spontaneously or with treatment.

Causes

The exact cause of asthma is not fully understood, but it is believed to result from a combination of genetic and environmental factors.

- Genetic Factors:

- Family history of asthma or other allergic conditions such as eczema or hay fever.

- Genetic predisposition to developing hypersensitivity to environmental allergens.

- Environmental Factors:

- Allergens: Such as pollen, dust mites, pet dander, moulds, and cockroach droppings.

- Irritants: Including tobacco smoke, air pollution, chemical fumes, and strong odours.

- Respiratory Infections: Particularly in early childhood.

- Physical Activity: Exercise-induced asthma.

- Weather Conditions: Cold air or sudden changes in weather.

- Medications: Such as aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Signs & Symptoms

Asthma symptoms can vary from person to person and may include:

- Wheezing: A high-pitched whistling sound when breathing, particularly on exhalation.

- Shortness of Breath: Difficulty breathing, often accompanied by feelings of suffocation.

- Chest Tightness: A feeling of constriction or pressure in the chest.

- Coughing: Persistent cough, often worse at night or early morning.

Pathophysiology

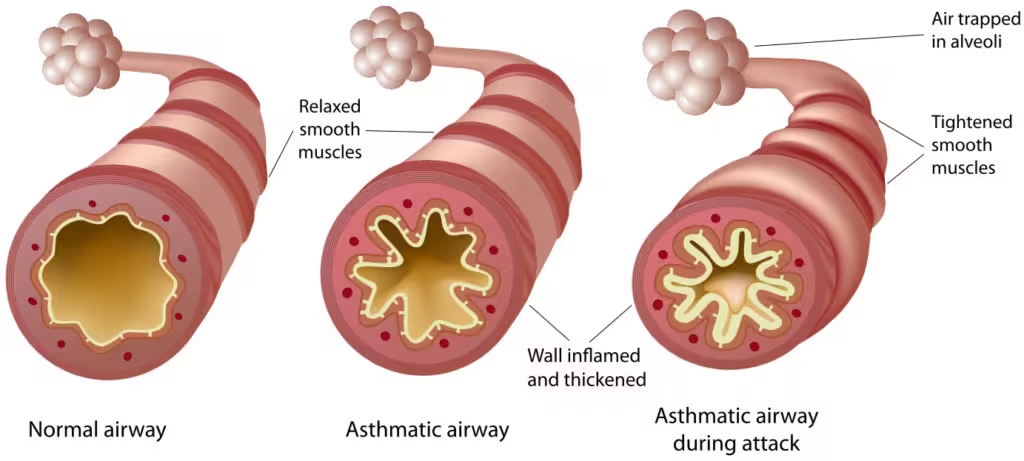

The pathophysiology of asthma involves chronic inflammation of the airways, leading to airway hyperresponsiveness and airflow obstruction.

- Chronic Inflammation:

- Inflammatory cells, such as eosinophils, T lymphocytes, and mast cells, infiltrate the airway walls.

- Inflammatory mediators, including cytokines, leukotrienes, and histamine, are released, causing swelling and increased mucus production.

- Airway Hyperresponsiveness:

- The inflamed airways become hyperresponsive to various triggers such as allergens, irritants, and exercise.

- This hyperresponsiveness leads to bronchoconstriction, a tightening of the muscles around the airways.

- Airflow Obstruction:

- The combination of inflammation, bronchoconstriction, and increased mucus production results in airflow obstruction.

- This obstruction is variable and can be partially or fully reversible with appropriate treatment.

Management

Management of asthma focuses on controlling symptoms, reducing the frequency and severity of exacerbations, and improving quality of life. The British Thoracic Society (BTS) and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) provide guidelines for asthma management.

- Lifestyle Modifications:

- Avoiding Triggers: Identifying and avoiding known triggers such as allergens and irritants.

- Smoking Cessation: Essential for all patients to reduce asthma severity and improve lung function.

- Medications:

- Reliever Inhalers (Short-acting beta2 agonists):

- Examples: Salbutamol (Ventolin), Terbutaline (Bricanyl).

- Mechanism of Action: These medications work by stimulating beta2 receptors in the smooth muscle of the airways, causing relaxation and bronchodilation. This leads to immediate relief of bronchoconstriction and alleviation of symptoms such as wheezing, breathlessness, and chest tightness.

- Usage: Used as needed for quick relief of acute asthma symptoms. They act within minutes, and their effects can last for 4-6 hours.

- Considerations: Over-reliance on reliever inhalers may indicate poorly controlled asthma, necessitating a review of the patient’s asthma management plan.

- Preventer Inhalers (Inhaled corticosteroids):

- Examples: Beclometasone (Qvar), Budesonide (Pulmicort), Fluticasone (Flixotide).

- Mechanism of Action: Inhaled corticosteroids reduce airway inflammation by decreasing the production of inflammatory mediators, reducing airway hyperresponsiveness, and preventing long-term airway remodelling.

- Usage: Taken daily as maintenance therapy to prevent asthma symptoms and reduce the frequency and severity of exacerbations.

- Considerations: It may take a few weeks for the full effects to be noticeable. Rinsing the mouth after use is recommended to prevent oral thrush, a common side effect.

- Long-acting Beta2 Agonists (LABAs):

- Examples: Salmeterol (Serevent), Formoterol (Foradil).

- Mechanism of Action: Similar to short-acting beta2 agonists, LABAs stimulate beta2 receptors but have a longer duration of action, lasting up to 12 hours or more.

- Usage: LABAs are used in combination with inhaled corticosteroids for patients whose asthma is not adequately controlled with corticosteroids alone. They help in maintaining long-term control and preventing nocturnal symptoms.

- Considerations: LABAs should not be used as monotherapy due to the risk of worsening asthma control and should always be combined with inhaled corticosteroids.

- Leukotriene Receptor Antagonists (LTRAs):

- Examples: Montelukast (Singulair), Zafirlukast (Accolate).

- Mechanism of Action: LTRAs block leukotriene receptors in the airways, preventing leukotrienes from causing bronchoconstriction, inflammation, and mucus production.

- Usage: Taken orally, often in addition to inhaled corticosteroids, for long-term control and prevention of asthma symptoms. Particularly useful for patients with allergic rhinitis and exercise-induced asthma.

- Considerations: Generally well-tolerated but may cause side effects such as headaches, abdominal pain, and mood changes.

- Theophylline:

- Examples: Theophylline (Uniphyllin, Slo-Phyllin).

- Mechanism of Action: Theophylline is a bronchodilator that relaxes the smooth muscles of the airways by inhibiting phosphodiesterase enzymes and increasing cyclic AMP levels.

- Usage: Used as an add-on therapy for patients with severe asthma that is not fully controlled by inhaled medications. It is available in oral and intravenous forms.

- Considerations: Requires regular blood level monitoring due to its narrow therapeutic range and potential side effects such as nausea, insomnia, and arrhythmias.

- Biologic Therapies:

- Examples: Omalizumab (Xolair), Mepolizumab (Nucala), Benralizumab (Fasenra).

- Mechanism of Action: Biologics target specific molecules involved in the asthma inflammatory pathway. For example, omalizumab binds to IgE, preventing it from triggering allergic responses, while mepolizumab and benralizumab target interleukin-5 (IL-5), reducing eosinophilic inflammation.

- Usage: Administered via injection, biologics are used for patients with severe asthma that is not controlled with standard treatments. They help in reducing the frequency of exacerbations and improving overall asthma control.

- Considerations: These treatments are usually reserved for severe cases due to their cost and the need for specialised administration. Patients require monitoring for potential side effects, including allergic reactions.

- Reliever Inhalers (Short-acting beta2 agonists):

- Monitoring and Follow-Up:

- Regular follow-up appointments to assess asthma control and adjust treatment as necessary.

- Use of peak flow meters or spirometry to monitor lung function.

- Asthma Action Plan:

- A personalised action plan developed in consultation with healthcare providers to manage asthma symptoms and exacerbations.

- Education and Self-Management:

- Educating patients about their condition and proper use of inhalers.

- Encouraging adherence to treatment plans and recognising early signs of exacerbations.

- Pulmonary Rehabilitation:

- Exercise training, education, and support for patients with severe asthma to improve physical conditioning and quality of life.

Nursing Management

- Continuous Monitoring:

- Continuous monitoring of vital signs, including heart rate, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation (SpO2), and blood pressure.

- Regular assessment of lung sounds for wheezing, crackles, and breath sounds to detect airway obstruction or improvement.

- Monitoring arterial blood gases (ABGs) to assess oxygenation, ventilation status, and acid-base balance.

- Neurological Status:

- Monitoring for signs of hypoxia, such as restlessness, confusion, or altered mental status.

- Oxygen Therapy:

- Providing supplemental oxygen to maintain SpO2 between 94-96% (or as prescribed).

- Using high-flow oxygen or non-invasive ventilation (NIV) if necessary to improve oxygenation and reduce the work of breathing.

- Magnesium Sulfate:

- Administering intravenous magnesium sulfate in severe cases to relax bronchial muscles and improve airflow.

- Antibiotics:

- Administering antibiotics if a bacterial infection is suspected or confirmed.

Respiratory Support

- Non-Invasive Ventilation (NIV):

- Using NIV (e.g., CPAP or BiPAP) to improve ventilation and reduce the work of breathing in patients with severe respiratory distress.

- Mechanical Ventilation:

- Initiating mechanical ventilation for patients with impending respiratory failure or those who do not respond to NIV.

- Managing ventilator settings to avoid barotrauma and volutrauma, ensuring adequate sedation and analgesia.

Hydration and Nutrition

- Fluid Management:

- Monitoring fluid balance and administering intravenous fluids as needed to maintain hydration.

- Avoiding overhydration, which can worsen pulmonary edema and respiratory distress.

- Nutritional Support:

- Providing enteral or parenteral nutrition to meet the patient’s metabolic needs.

- Monitoring for signs of aspiration, especially in ventilated patients.

Patient Education and Support

- Education:

- Educating the patient and family about asthma management, including trigger avoidance and proper inhaler technique.

- Explaining the importance of adherence to prescribed medications and follow-up care.

- Emotional Support:

- Providing reassurance and emotional support to alleviate anxiety and stress.

- Involving the family in the care plan and offering support resources.

Prevention of Complications

- Infection Control:

- Adhering to strict infection control practices to prevent hospital-acquired infections.

- Monitoring for signs of infection and administering appropriate prophylactic measures.

- VTE Prophylaxis:

- Implementing measures to prevent venous thromboembolism (VTE), such as pharmacological prophylaxis and encouraging early mobilization if possible.

Multidisciplinary Collaboration

- Working closely with respiratory therapists, pulmonologists, intensivists, and other healthcare professionals to provide comprehensive care.

- Regularly reviewing and updating the care plan based on the patient’s progress and response to treatment.

References: