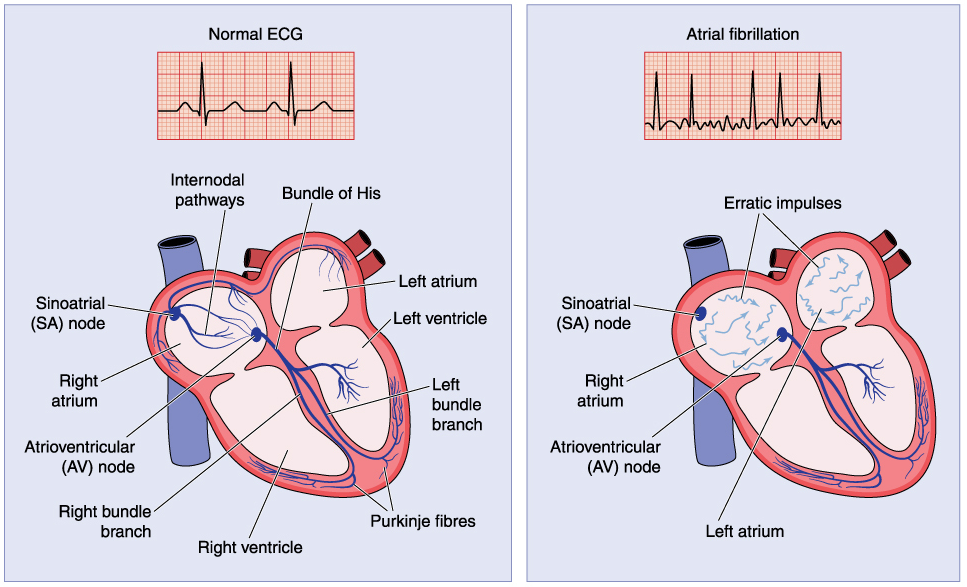

Atrial fibrillation (often abbreviated as Afib or AF) is a common type of

cardiac arrhythmia, characterised by disorganised electrical activity in the atria leading to ineffective atrial contraction and an irregular, often rapid, ventricular response. This condition can significantly impact cardiac function and increase the risk of stroke and other cardiovascular complications

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of atrial fibrillation (Afib) is complex and not fully understood, but it’s generally believed to involve two key factors:

- Triggers: These initiate the electrical signals that cause the chaotic firing in the atria.

- Substrate: This refers to the underlying condition of the atrial tissue that makes it susceptible to maintaining the irregular rhythm.

Here’s a breakdown of these factors:

Triggers:

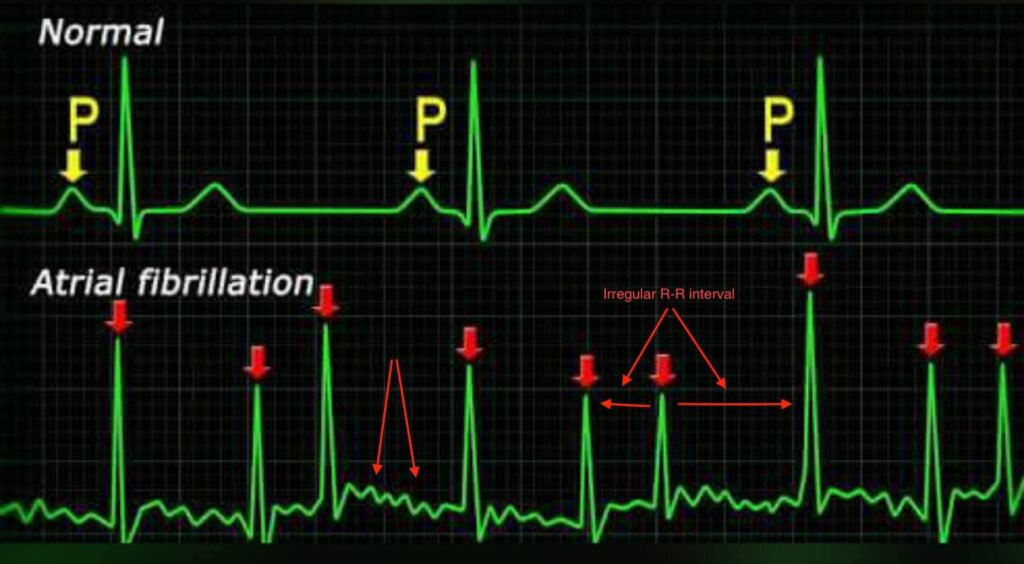

- Ectopic foci: These are abnormal areas in the atria that can fire electrical impulses independently, disrupting the normal coordinated contraction. Common locations include the pulmonary veins where they connect to the atria.

- Triggers from other sources: Conditions like lung disease, sleep apnea, or thyroid disorders can trigger Afib episodes through various mechanisms.

Substrate:

- Atrial remodeling: Over time, various factors like high blood pressure, aging, or underlying heart disease can cause structural and electrical changes in the atria. This remodeling makes the atria more susceptible to developing and sustaining Afib.

- Electrical remodeling: Changes in the way electrical impulses travel through the atria can contribute to Afib. This can involve altered action potentials (electrical signals within heart cells) or abnormal conduction pathways.

- Re-entry circuits: These are loops within the atria where electrical impulses can keep circling back on themselves, perpetuating the irregular rhythm. Atrial remodeling can create these circuits.

Causes

Several factors can contribute to atrial fibrillation, including:

- Underlying heart disease: Conditions like coronary artery disease, heart valve problems, or previous heart attack can damage heart tissue and increase the risk of Afib.

- High blood pressure (hypertension): Chronically high blood pressure can put stress on the heart and contribute to Afib development.

- Overactive thyroid: An overactive thyroid gland can disrupt electrical signals in the heart and potentially lead to Afib.

- Sleep apnea: This sleep disorder can cause intermittent oxygen deprivation during sleep, which can stress the heart and contribute to Afib.

- Electrolyte imbalances: Abnormal levels of electrolytes like potassium or magnesium can affect electrical conduction in the heart and trigger Afib.

- Stimulants: Excessive intake of caffeine or certain medications can act as stimulants and contribute to Afib in some cases.

- Congenital heart defects: In rare cases, some people might be born with a heart defect that predisposes them to Afib.

- Lifestyle factors: Obesity, excessive alcohol consumption, and lack of physical activity can also increase the risk of Afib.

Types of Atrial Fibrillation:

Atrial fibrillation can be categorised based on its duration:

- Paroxysmal Afib: Episodes come and go, lasting from seconds to hours, and then the heart rhythm returns to normal on its own.

- Persistent Afib: Episodes last longer than 7 days and may require medical intervention to restore a normal rhythm.

- Long-standing persistent Afib: Afib has been present for more than a year.

- Permanent Afib: The heart rhythm cannot be restored to normal, and the focus becomes managing the condition and preventing complications.

Symptoms:

Atrial fibrillation can present in various ways. Some people might not experience any noticeable symptoms at all, while others might have:

- Palpitations: A fluttering or racing sensation in the chest, often described as an irregular heartbeat.

- Shortness of breath: Difficulty catching your breath, especially during exertion.

- Fatigue: Feeling unusually tired or lacking energy.

- Lightheadedness or dizziness: A sensation of near fainting or feeling lightheaded.

- Chest pain: Less commonly, some people might experience chest pain during an Afib episode.

Diagnostic Criteria

AF is diagnosed through a combination of clinical assessment and diagnostic tests:

- Electrocardiogram (ECG): Absence of distinct P waves and presence of irregularly irregular R-R intervals, often with a wavy or erratic baseline.

- Holter Monitor: Continuous ECG monitoring over 24-48 hours to capture intermittent AF episodes.

- Echocardiogram: Ultrasound imaging to assess structural heart disease, atrial size, and function.

- Blood Tests: Evaluation of thyroid function and electrolyte levels to identify reversible causes

Management of Atrial Fibrillation as per NICE Guidelines (CG180)

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) provides specific guidelines under CG180 for the management of atrial fibrillation (AF). These guidelines aim to improve patient outcomes by providing evidence-based recommendations for the diagnosis, assessment, and treatment of AF.

Initial Assessment and Diagnosis

- History and Examination:

- Document patient symptoms, history of palpitations, dizziness, syncope, and other related symptoms.

- Identify underlying causes and comorbid conditions such as hypertension, heart failure, and thyroid disease.

- Diagnostic Testing:

- 12-Lead ECG: To confirm the diagnosis of AF.

- Echocardiogram: To assess cardiac structure and function.

- Blood Tests: Including thyroid function, renal function, and electrolyte levels.

Acute Management of AF

Management of Atrial Fibrillation as per NICE Guidelines (CG180)

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) provides comprehensive guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation (AF) in the UK under CG180. These guidelines cover the diagnosis, assessment, and treatment of AF, aiming to reduce the risk of stroke and other complications while improving patient outcomes.

Initial Assessment and Diagnosis

- Patient History and Physical Examination:

- Document patient symptoms, history of palpitations, dizziness, syncope, and other related symptoms.

- Identify underlying causes and comorbid conditions such as hypertension, heart failure, and thyroid disease.

- Diagnostic Testing:

- 12-Lead ECG: To confirm the diagnosis of AF.

- Echocardiogram: To assess cardiac structure and function.

- Blood Tests: Including thyroid function, renal function, and electrolyte levels.

Management Strategies

The management of AF involves several key components: rate control, rhythm control, anticoagulation, electrolyte replacement, and lifestyle modifications.

1. Acute Management of AF

A. Rate control

Rate control aims to manage the heart rate to alleviate symptoms and prevent tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy.

- First-Line Medications:

- Beta-Blockers: e.g., bisoprolol, metoprolol.

- Rate-Limiting Calcium Channel Blockers: e.g., diltiazem, verapamil.

- Second-Line Medications:

- Digoxin: Consider in sedentary patients or those with heart failure.

- Combination Therapy: If monotherapy is inadequate, consider combining drugs, ensuring careful monitoring for side effects

B. Rhythm Control:

- Medications for pharmacological cardioversion (e.g., amiodarone, flecainide).

- Electrical Cardioversion:

- Consider in patients with recent-onset AF, haemodynamic instability, or if pharmacological cardioversion fails.

C . Electrolyte Replacement:

Electrolyte imbalances, especially low levels of potassium and magnesium, can predispose patients to AF. Correcting these imbalances is crucial for both rate and rhythm control

Long-Term Management and Prevention

2. Anticoagulation

Anticoagulation is critical for stroke prevention in AF patients, assessed using the CHA2DS2-VASc score.

- Risk Assessment:

- CHA2DS2-VASc Score:

- 0: No anticoagulation.

- 1: Consider anticoagulation.

- ≥2: Strongly recommend anticoagulation.

- CHA2DS2-VASc Score:

- Anticoagulation Options:

- Vitamin K Antagonists (VKAs): e.g., warfarin (monitor INR regularly).

- Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOACs): e.g., apixaban, rivaroxaban, dabigatran, edoxaban (preferred due to fewer monitoring requirements).

- Bleeding Risk Assessment:

- Use the HAS-BLED score to evaluate bleeding risk and manage modifiable risk factors.

Catheter Ablation:

- Recommended for patients with symptomatic paroxysmal AF that is refractory to medical therapy or those preferring an interventional approach.

- Pulmonary vein isolation is the standard procedure.

Pulmonary veins (PVs) play a significant role in the development of atrial fibrillation (AFib), an irregular heart rhythm:

- Ectopic activity: PV muscle fibers can trigger AFib by originating extra beats.

- Spontaneous depolarisation: PV activity may initiate or sustain AFib through spontaneous depolarisation or re-entry.

- PV diameter: An increase in PV diameter may trigger AFib.

- A doctor may recommend pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) as a treatment for AFib if medications aren’t effective or if AFib ends on its own. PVI is a type of cardiac ablation that uses heat or cold energy to create small scars in the heart that block irregular electrical signals and restore a regular heartbeat.

Lifestyle Modifications and Management of Underlying Conditions:

- Address contributing factors, such as hypertension, diabetes, hyperthyroidism, and lifestyle factors.

- Encourage dietary modifications to maintain adequate levels of electrolytes.