A healthy heart acts like a pump, constantly circulating blood that carries oxygen and nutrients to your organs. In cardiogenic shock, the heart muscle weakens, significantly reducing its pumping ability. This sets off a chain reaction

Reduced Cardiac Output > Starved Organs > Cellular Damage

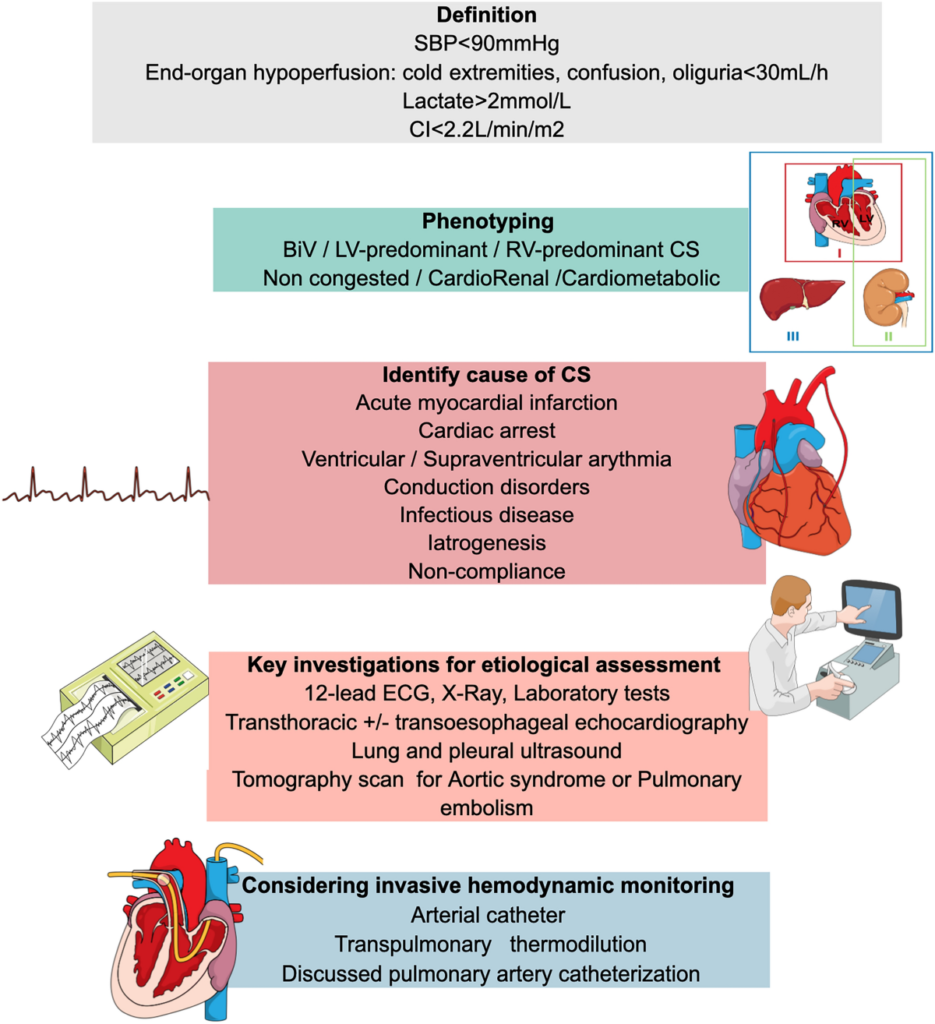

Definition:

Cardiogenic shock is a life-threatening condition characterised by the heart’s inability to pump sufficient blood to meet the body’s needs, leading to inadequate tissue perfusion and oxygen delivery. It is most commonly caused by a severe heart attack but can also result from other cardiac conditions.

Criteria for Cardiogenic Shock

Clinical criteria:

- Systolic blood pressure ≤ 90 mm Hg sustained for at least 30 minutes, or requiring intervention to maintain a systolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mm Hg.

- Urine output ≤ 30 mL/hr.

- Presence of cool extremities indicating poor perfusion.

Hemodynamic criteria:

- Reduced cardiac index, defined as ≤ 2.2 liters per minute per square meter of body surface area.

- Cardiac index (CI) is a hemodynamic measurement that compares the heart’s performance to an individual’s size by relating the left ventricle’s cardiac output per minute to their body surface area (BSA). The normal range for CI is 2.5 to 4 liters per minute per square meter (L/min/m2).

- Elevated pulmonary-capillary wedge pressure, exceeding 15 mm Hg.

- Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP), also known as pulmonary artery occlusion pressure (PAOP), is a haemodynamic parameter that estimates the pressure in the left atrium of the heart. The normal pulmonary capillary wedge pressure is between 4 to 12 mmHg

Pathophysiology:

The pathophysiology of cardiogenic shock involves several key mechanisms:

- Primary Cardiac Dysfunction:

- Myocardial Infarction: The most common cause, is where a significant portion of the heart muscle is damaged due to blocked coronary arteries.

- Heart Failure: Severe, chronic heart failure can deteriorate to cardiogenic shock.

- Cardiac Arrhythmias: Abnormal heart rhythms, such as ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation, can severely impair cardiac output.

- Pulmonary Embolism: Blockage in the pulmonary arteries can lead to right ventricular failure and subsequently cardiogenic shock.

- Drug Overdose or Poisoning: Certain drugs and toxins can depress cardiac function and lead to shock.

- Mechanical defects:

- Cardiac Tamponade: Accumulation of fluid in the pericardium that compresses the heart and reduces its pumping ability.

- Acute Mitral Regurgitation: Caused by the rupture of a papillary muscle.

- Ventricular Wall Rupture: This can involve either the septal wall or the free wall of the ventricle

- Left Ventricular Outflow Obstruction :

- Hypertrophic Obstructive Cardiomyopathy (HOCM): A condition where the heart muscle becomes abnormally thick, particularly affecting the interventricular septum, which obstructs blood flow.

- Aortic stenosis: is the narrowing of the aortic valve opening, which restricts blood flow from the left ventricle to the aorta.

2. Decreased Cardiac Output:

- Reduced Stroke Volume: Damage to the heart muscle decreases the force of contraction, reducing the volume of blood ejected with each heartbeat.

- Increased Afterload: High resistance in the arteries can further impair the heart’s ability to pump blood.

3. Systemic Hypoperfusion:

- Inadequate Tissue Perfusion: Reduced cardiac output leads to decreased blood flow to vital organs, causing hypoxia and metabolic acidosis.

- Organ Dysfunction: Prolonged hypoperfusion results in multi-organ dysfunction, including renal failure, hepatic failure, and altered mental status.

4. Neurohormonal Activation:

- Compensatory Mechanisms: The body attempts to compensate for reduced cardiac output by increasing heart rate and vascular resistance, which can worsen the heart’s workload.

- Sympathetic Nervous System: Activation leads to increased heart rate and vasoconstriction, which can worsen myocardial oxygen demand and ischemia.

- Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS): Activation increases blood volume and vascular resistance, further stressing the failing heart.

Identification:

Early recognition of cardiogenic shock is essential for effective treatment. Identification involves clinical assessment and diagnostic testing:

- Clinical Symptoms:

- Chest pain or discomfort (Angina)

- Rapid breathing (tachypnoea)

- Severe shortness of breath (dyspnoea)

- Weak pulse and low blood pressure (hypotension)

- Cold, clammy skin

- Confusion or altered mental state

- Reduced urine output (oliguria)

2. Physical Examination:

- Signs of poor perfusion (e.g., cyanosis, mottled skin)

- Elevated jugular venous pressure

- Pulmonary crackles (indicative of pulmonary congestion)

- Weak peripheral pulses

3. Diagnostic Tests:

- Electrocardiogram (ECG): Identifies ischaemic changes or arrhythmias.

- Echocardiography: Assesses cardiac function, wall motion abnormalities, and valvular function.

- Haemodynamic Monitoring: Measures cardiac output, systemic vascular resistance, and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure using tools like a pulmonary artery catheter.

- Blood Tests: Elevated cardiac biomarkers (e.g., troponin), arterial blood gases, lactate levels, and markers of organ function (e.g., creatinine, liver enzymes).

Management:

Management of cardiogenic shock focuses on stabilising the patient, improving cardiac function, and addressing the underlying cause:

- Initial Stabilisation:

- Oxygen Therapy: Ensures adequate oxygenation and reduces myocardial oxygen demand.

- Fluid Management: Careful administration of intravenous fluids to optimise preload without causing fluid overload.

- Vasoactive Agents:

- Norepinephrine: Preferred for severe hypotension (systolic BP < 70 mm Hg) or when unresponsive to other medications. Caution is needed in myocardial infarction patients due to the risk of tachycardia and increased myocardial oxygen demand.

- Dobutamine: Improves myocardial contractility and cardiac output through beta-1 and beta-2 agonist properties.

- Milrinone: Reduces left ventricular filling pressures and is commonly used for its inotropic effects.

- Furosemide: Decreases plasma volume and edema, reducing cardiac output and blood pressure initially but leading to a compensatory increase in peripheral vascular resistance.

2. Addressing Underlying Cause:

- Revascularisation: Emergency percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) for myocardial infarction.

- Antiarrhythmic Therapy: Management of arrhythmias with medications or electrical cardioversion.

- Surgical Interventions: Repair of valvular dysfunction or structural abnormalities if needed.

- Fibrinolytic Therapy: Indicated for patients who are not candidates for percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), provided there are no contraindications.

- Antiplatelet Therapy: Aspirin and/or ticagrelor/Clopidogrel, Used in myocardial infarction or acute coronary syndrome (STEMI/NSTEMI) to reduce mortality.

3. Mechanical Support:

- Intra-Aortic Balloon Pump (IABP): Temporarily supports cardiac output and reduces myocardial oxygen demand.

- Ventricular Assist Devices (VADs): Provides longer-term mechanical support for severe cases.

- Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO): Supports both cardiac and respiratory function in critical situations.

4. Long-term Management:

- Medications: Ongoing use of medications such as beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, or aldosterone antagonists to support heart function.

- Lifestyle Modifications: Recommendations for diet, exercise, smoking cessation, and weight management.

- Monitoring and Follow-up: Regular follow-up with a cardiologist to monitor heart function and adjust treatment as needed.

Conclusion:

Early identification and prompt, aggressive treatment are crucial to improving outcomes in patients with cardiogenic shock. Comprehensive management involves stabilising haemodynamics, addressing the underlying cause, and providing ongoing support to prevent recurrence and improve overall cardiac health.

References: