Abdominal hypertension, also known as intra-abdominal hypertension (IAH), is a condition characterised by elevated pressure within the abdominal cavity. It can lead to significant morbidity and mortality due to its impact on abdominal organs and systemic circulation.

- Normal: Less than 5 mmHg

- IAH: Greater than or equal to 12 mmHg (persistent)

Categories of IAH :

- Grade I: IAP 12-15 mmHg (Mild)

- Grade II: IAP 16-20 mmHg (Moderate)

- Grade III: IAP 21-25 mmHg (Severe)

- Grade IV: IAP >25 mmHg (Very Severe)

Definition

- Intra-Abdominal Hypertension (IAH): A sustained or repeated pathological elevation of intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) equal to or greater than 12 mmHg.

- Abdominal Compartment Syndrome (ACS): A severe form of IAH where the intra-abdominal pressure exceeds 20 mmHg and is associated with new organ dysfunction or failure.

Causes

IAH can result from a variety of conditions that increase intra-abdominal volume or decrease abdominal wall compliance:

- Increased Intra-Abdominal Volume:

- Ascites: Accumulation of fluid in the abdominal cavity.

- Hemoperitoneum: Presence of blood in the peritoneal cavity.

- Massive fluid resuscitation: Large volumes of fluid administered intravenously, commonly seen in critical care settings.

- Bowel distension: Due to obstruction, ileus, or infection.

- Decreased Abdominal Wall Compliance:

- Obesity: Excess adipose tissue increases abdominal pressure.

- Abdominal trauma: Injury leading to swelling and bleeding within the abdominal cavity.

- Postoperative conditions: Abdominal surgery can reduce compliance due to pain, muscle dysfunction, or dressings.

Pathophysiology

Elevated intra-abdominal pressure can compress abdominal organs, impairing their function and leading to systemic effects:

- Organ Compression:

- Kidneys: Reduced renal perfusion leading to acute kidney injury.

- Liver: Impaired hepatic blood flow causing liver dysfunction.

- Gut: Decreased mesenteric blood flow leading to bowel ischemia and necrosis.

- Systemic Effects:

- Cardiovascular: Increased intra-thoracic pressure, reduced venous return, and cardiac output.

- Respiratory: Diaphragmatic elevation leading to reduced lung volumes and compliance, resulting in respiratory distress.

- Central Nervous System: Increased intracranial pressure due to impaired venous return from the brain.

Methods of Measuring Intra-Abdominal Pressure (IAP)

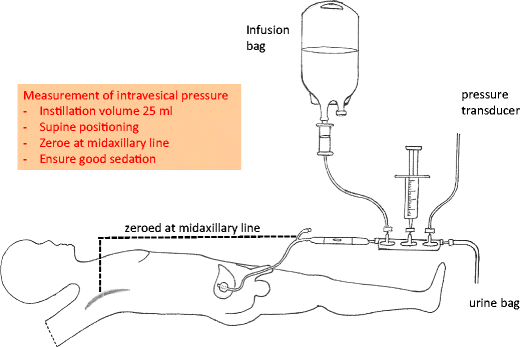

- Trans-Bladder (Intravesical) Pressure Measurement

- Procedure:

- A Foley catheter is inserted into the bladder.

- The bladder is partially filled with a sterile saline solution (typically 50-100 mL).

- A pressure transducer is connected to the catheter, and the patient is positioned supine.

- The pressure is measured at the end of expiration to avoid fluctuations due to respiratory movements.

- Advantages:

- Non-invasive and relatively simple to perform.

- Widely accepted as the standard method for IAP measurement.

- Considerations:

- Ensuring the bladder is not overfilled is critical, as this can affect accuracy.

- Procedure:

- Trans-Gastric Pressure Measurement

- Procedure:

- A nasogastric tube is placed into the stomach.

- The tube is connected to a pressure transducer.

- Measurements are taken similarly to the trans-bladder method, ensuring the patient is in a supine position and measurements are taken at end-expiration.

- Advantages:

- Useful in patients where bladder catheterisation is contraindicated.

- Considerations:

- Less commonly used than the trans-bladder method.

- May be less accurate due to potential complications with gastric contents.

- Procedure:

- Direct Intraperitoneal Pressure Measurement

- Procedure:

- Performed during surgery or via a percutaneous catheter placed directly into the abdominal cavity.

- A pressure transducer is attached directly to the catheter to measure the intra-abdominal pressure.

- Advantages:

- Provides a direct and highly accurate measurement of IAP.

- Considerations:

- Invasive and typically reserved for surgical settings.

- Procedure:

- Rectal Pressure Measurement

- Procedure:

- A rectal catheter is inserted, and a pressure transducer is used to measure IAP.

- Advantages:

- Another alternative when bladder or gastric measurements are not feasible.

- Considerations:

- Not widely used and may have varying accuracy depending on patient condition.

- Procedure:

Clinical Management

Management of IAH and ACS involves both medical and surgical approaches:

- Medical Management:

- Fluid Management: Careful regulation of intravenous fluids to avoid over-resuscitation.

- Diuretics: Used to reduce fluid accumulation.

- Paracentesis: Removal of excess abdominal fluid in cases of ascites.

- Surgical Management:

- Decompression Laparotomy: Emergency surgery to relieve pressure in severe cases.

- Abdominal Wall Reconstruction: For cases where decreased abdominal compliance is due to structural issues.

- Supportive Care:

- Optimising Ventilation: Mechanical ventilation adjustments to improve respiratory function.

- Monitoring and Support: Continuous monitoring of organ function and prompt treatment of organ failure.