Left ventricular failure (LVF), often referred to as left-sided heart failure, occurs when the left ventricle, the heart’s primary pumping chamber, weakens and struggles to pump blood efficiently throughout the body. This can lead to a buildup of fluid in the lungs and other organs, causing various symptoms and potentially life-threatening complications.

This condition can be categorised into two types: systolic heart failure (where the heart muscle doesn’t contract forcefully enough) and diastolic heart failure (where the heart muscle is stiff and doesn’t fill properly).

In systolic heart failure, the reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) indicates that the heart cannot pump with enough force to push sufficient blood into circulation. Diastolic heart failure, on the other hand, involves heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), where the heart’s pumping function is normal, but its relaxation and filling phases are impaired

Pathophysiology: The pathophysiology of left ventricular failure involves several key mechanisms:

- Decreased Contractility:

- Ischaemic Heart Disease: The most common cause, where reduced blood supply to the heart muscle leads to myocardial infarction or chronic ischaemia.

- Cardiomyopathy: Diseases of the heart muscle, such as dilated cardiomyopathy, which weaken its ability to contract effectively.

- Myocarditis: Inflammation of the heart muscle can also reduce contractility.

- Increased Afterload:

- Hypertension: Long-standing high blood pressure increases the workload on the left ventricle.

- Aortic Stenosis: Narrowing of the aortic valve increases resistance against which the left ventricle must pump.

- Increased Preload:

- Volume Overload: Conditions like aortic regurgitation cause blood to flow back into the left ventricle from the aorta during diastole, leading to increased blood volume in the ventricle. This increased volume stretches the ventricular muscle beyond its optimal capacity, reducing its efficiency.

- Mitral Regurgitation: Here, blood leaks back into the left atrium during systole, causing increased volume load on the left ventricle during subsequent diastole, leading to similar stretching effects.

- Structural Changes:

- Left Ventricular Hypertrophy: Chronic pressure overload leads to thickening of the heart muscle, which can eventually impair its function.

- Dilated Cardiomyopathy: The left ventricle enlarges, and its walls become thin and weak, reducing its pumping ability.

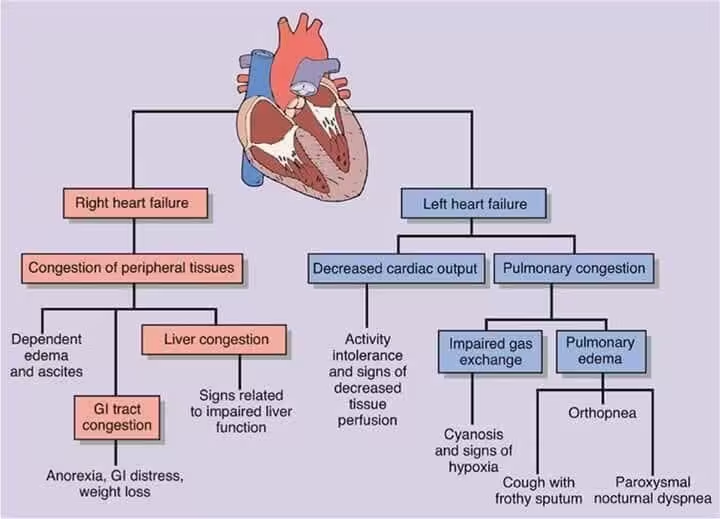

Clinical Features: The symptoms of left ventricular failure are primarily due to reduced cardiac output and pulmonary congestion:

- Dyspnoea (Shortness of Breath):

- Exertional Dyspnoea: Difficulty breathing during physical activity.

- Orthopnoea: Difficulty breathing while lying flat.

- Paroxysmal Nocturnal Dyspnoea: Sudden episodes of severe shortness of breath at night.

- Fatigue and Weakness:

- Due to reduced oxygen supply to muscles and organs.

- Pulmonary Congestion:

- Cough: Often productive of frothy sputum.

- Wheezing: Due to fluid in the lungs.

- Crackles/Rales: Heard on auscultation of the lungs.

- Peripheral Oedema:

- Swelling of the legs and ankles, although more characteristic of right-sided heart failure, can occur in advanced LVF.

Diagnosis: Diagnosis of left ventricular failure involves a combination of clinical evaluation, imaging, and laboratory tests:

- Clinical Examination:

- Auscultation: Listening for crackles in the lungs and heart murmurs.

- Jugular Venous Pressure: Can be elevated in severe cases.

- Imaging:

- Echocardiogram: To assess left ventricular size, wall thickness, and ejection fraction.

- Chest X-ray: To detect pulmonary congestion and cardiomegaly.

- Laboratory Tests:

- B-type Natriuretic Peptide (BNP): Elevated levels indicate heart failure.

- Troponins: To rule out myocardial infarction.

- Renal Function Tests: To assess for kidney involvement.

Management: Management of left ventricular failure aims to relieve symptoms, improve quality of life, and prolong survival. The management strategies are prioritised as follows:

- Medical Management:

- ACE Inhibitors/ARBs: To reduce afterload and improve survival.

- Beta-Blockers: To reduce heart rate and myocardial oxygen demand.

- Diuretics: To reduce fluid overload.

- Aldosterone Antagonists: For additional fluid control and survival benefit.

- Digitalis: In selected cases to improve contractility.

- Surgical and Device Therapy:

- Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting (CABG): For patients with coronary artery disease.

- Valve Repair or Replacement: For patients with significant valvular disease.

- Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator (ICD): For patients at risk of sudden cardiac death.

- Cardiac Resynchronisation Therapy (CRT): For patients with significant dyssynchrony in ventricular contraction.

- Left Ventricular Assist Device (LVAD): As a bridge to transplant or for long-term support in select patients.

- Heart Transplantation: For end-stage heart failure.

- Lifestyle Modifications:

- Dietary Changes: Low-sodium diet to reduce fluid retention.

- Exercise: Tailored exercise programmes to improve cardiovascular health.

- Smoking Cessation: To improve overall heart health.

Conclusion: Left ventricular failure is a serious condition that requires a comprehensive approach to management. Early recognition and treatment are crucial to improve outcomes and quality of life for patients.

References: