Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is a type of hospital-acquired pneumonia that develops in patients who have been on mechanical ventilation through an endotracheal or tracheostomy tube for at least 48 hours. It is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in the intensive care unit (ICU).

Causes

VAP is primarily caused by bacterial infections, with common pathogens including:

- Gram-negative bacteria:

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Escherichia coli

- Klebsiella pneumoniae

- Acinetobacter spp.

- Gram-positive bacteria:

- Staphylococcus aureus (including MRSA)

- Other pathogens:

- Enterobacteriaceae

- Legionella pneumophila

Risk Factors

- Prolonged mechanical ventilation

- Aspiration of oropharyngeal secretions

- Use of sedatives and muscle relaxants

- Prior antibiotic therapy

- Underlying chronic lung disease

- Immunosuppression

Signs & Symptoms

- Fever and chills

- Increased respiratory secretions, often purulent

- Worsening gas exchange (hypoxaemia)

- Increased respiratory rate

- Increased white blood cell count

- New or progressive infiltrates on chest X-ray

Pathophysiology

- Colonisation and Aspiration:

- Endotracheal tubes bypass the body’s natural defence mechanisms, allowing direct entry of pathogens.

- Aspiration of contaminated secretions from the oropharynx or stomach can introduce bacteria into the lower respiratory tract.

- Biofilm Formation:

- Pathogens form biofilms on the surface of the endotracheal tube, which protect them from antibiotics and immune responses.

- Inflammatory Response:

- The presence of bacteria triggers an intense inflammatory response in the lungs.

- Inflammatory cells and fluid accumulate in the alveoli, leading to impaired gas exchange.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of VAP involves a combination of clinical, radiographic, and microbiological criteria:

- Clinical Criteria:

- New or progressive infiltrate on chest X-ray

- At least two of the following: fever, leukocytosis or leukopenia, purulent tracheal secretions.

- Microbiological Testing:

- Tracheal aspirate cultures

- Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) cultures

- Protected specimen brush (PSB) cultures

- Radiographic Imaging:

- Chest X-ray or CT scan showing new or worsening infiltrates.

Management

- Preventive Measures:

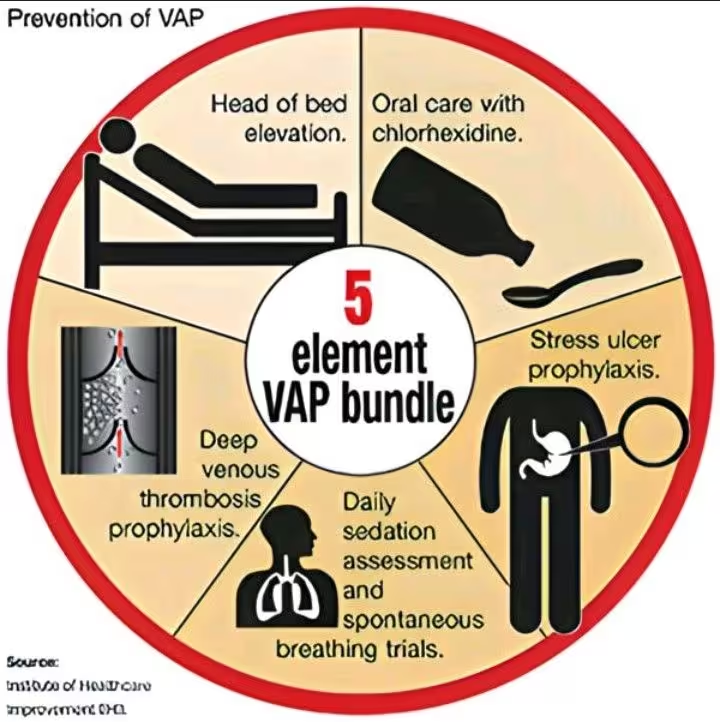

- Ventilator Bundle:

- Elevating the head of the bed to 30-45 degrees.

- Daily sedation vacations and assessment of readiness to extubate.

- Peptic ulcer disease prophylaxis.

- Deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis.

- Daily oral care with chlorhexidine.

- Hand Hygiene: Strict adherence to hand hygiene protocols.

- Aspiration Precautions: Proper cuff management and subglottic suctioning.

- Ventilator Bundle:

- Empirical Antibiotic Therapy:

- Initiate broad-spectrum antibiotics based on local antibiogram and suspected pathogens.

- Common choices include:

- Anti-pseudomonal beta-lactams: Piperacillin-tazobactam, cefepime.

- Carbapenems: Meropenem, imipenem.

- MRSA coverage: Vancomycin or linezolid.

- De-escalate therapy based on culture results and clinical response.

- Supportive Care:

- Continued mechanical ventilation with appropriate settings.

- Supplemental oxygen to maintain adequate oxygenation.

- Fluid management to ensure hemodynamic stability.

- Monitoring and Follow-Up:

- Regular assessment of respiratory status, oxygenation, and response to treatment.

- Adjust antibiotic therapy based on microbiological results and patient progress.

Outcomes

- Early identification and appropriate management of VAP are crucial to improve outcomes.

- Prolonged mechanical ventilation and ICU stay are associated with higher morbidity and mortality.

- Implementation of preventive measures can significantly reduce the incidence of VAP.